It’s never a good start to define things by negatives, by what they are not. But let’s get this straight: Steve Jobs is not a biopic.

Instead, it’s more like one of those true-stories-based-on-legend that Hollywood used to excel in making – like Davy Crockett – but less reverent of its eponymous hero and far more intelligent.

“This isn’t the Steve Jobs Story. And it was never intended to give you all the facts about Steve’s life,” says screenwriter Aaron Sorkin in an interview with Steven Levy.

Levy wrote extensively about Apple over decades for State-side publications like Newsweek, the New Yorker, the New York Times Magazine and Wired.

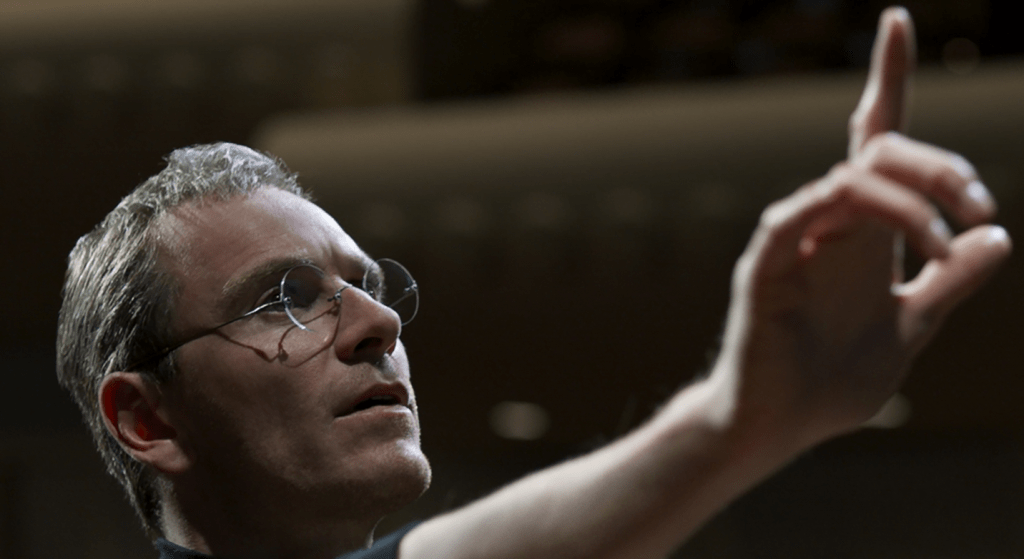

When Jobs was alive, Levy knew him as well as any person might. He takes Sorkin to task because so much of the film is fiction. It’s an accusation Sorkin doesn’t deny, pointing out that Michael Fassbender, who plays Jobs in the film, looks nothing like Jobs did in life.

But then Shakespeare’s Henry V is a work of fiction about a real king of England, and the women Picasso painted portraits of didn’t have seriously misaligned eyes as far as we know.

So if you’re expecting the tale of Saint Steve, patron saint of interface design, you’ll be disappointed. Likewise if you’re expecting Jobs to be unmasked as an ego monster devouring those around him. Rather, the film presents stories based on Jobs’ life and leaves the viewer to make up their own minds.

I never met Jobs, but I did hear him speak in the flesh, during his Jeremiah years, after Jon Scully had ousted him from his beloved Apple. Jobs was in London for the European launch of NeXT computer, a proprietary cube, black as Jobs’ turtleneck and the size of a mini-fridge. It was 1990.

As technology journalists, we were underwhelmed by the expensive box and wowed by the man. Charisma wasn’t half of it.

When Jobs went back to Apple, that cuboid and its bastard-grandson-of-Unix operating system became the template for the future generation of Macs running OSX. That must have taken some sales skills.

As the conduit for Sorkin’s screenplay, Fassbender convincingly conveys that force – Nietzsche called it “will”- as Jobs overcomes the human obstacles that stand in the way of him getting his own way down to the execution of minute detail.

There are no car chases, no explosions, no guns, no CGI monster eating nubile under-grads one by one in a deserted mental hospital. It’s a movie about people talking to each other. It did not break any box office records when it opened in the US.

So who is this film for? It helps if you know some computer industry history. There’s a discussion about the advantages of the Motorola 68000 microprocessor over the 6809. But I’m not sure Apple fans will enjoy the film.

Levy is probably best known for his book Insanely Great: The Life and Times of Macintosh, the Computer That Changed Everything, published in 1994. He clearly feels personally connected to – yea part of – the Apple story.

You can meet Apple customers who feel similar emotions. They would never countenance buying another brand of computer or phone; indeed, they would mortgage their first-born to own the latest Apple thing. I’ve met educated people who sincerely believe Apple wants to make the world a better place and who deny any profit motive.

The chances are they won’t like this film. So who does it appeal to?

The film is quite like a play: three acts based on three product launches, and a limited number of well-rounded supporting – and long-suffering – characters whose interactions with the protagonist reveal and develop his personality. Sorkin is, after all, a playwright first and screenwriter second.

Thus it’s an intelligent work of fiction, the voice of which deserves to be heard above the squealing of offended Apple fanboys.

Directed by Danny Boyle and written by Aaron Sorkin, Steve Jobs will release in UK cinemas 13 November. It stars Michael Fassbender, Kate Winslet, Seth Rogen, Jeff Daniels, Katherine Waterston and Michael Stuhlbarg.